The Fall of the Berlin Wall

Monday, 10 May 2021

Share this article:

By Gio A. – 1IB

Introduction

On August 13, 1961, construction workers began tearing up streets and erecting barriers in Berlin. This night marked the beginning of one of history’s most infamous dividing lines: the Berlin Wall. Construction continued for a decade as the wall cut through neighbourhoods, separated families, and divided not just Germany, but the world. (Jarausch)

Background Information

As World War II came to an end in 1945, the fate of Germany’s territory was decided at two Allied peace conferences in Yalta and Potsdam. They divided the vanquished nation into four “allied occupation zones”: The Soviet Union received the eastern half, while the United States, the United Kingdom, and (eventually) France received the western half. Despite the fact that Berlin was completely within the Soviet sector of the country (it was about 100 miles from the eastern-western occupation zone border), the Yalta and Potsdam agreements divided the city into similar sectors. The eastern half was taken by the Soviets, while the western half was taken by the other Allies. In June 1945, the four-way occupation of Berlin began.

The Blockade and Crisis

As Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev put it, the life of West Berlin, a conspicuously capitalist city deep within communist East Germany, “stuck like a bone in the Soviet throat.” The Russians started manoeuvring to force the US, the UK, and France out of the city permanently. A Soviet blockade of West Berlin was launched in 1948 with the aim of starving the western Allies out of the region. Instead of retreating, the US and its allies used the air to supply their respective sectors of the region. The Berlin Airlift, which lasted more than a year and delivered more than 2.3 million tons of food, fuel, and other supplies to West Berlin, was a huge success. In 1949, the Soviets lifted the blockade.

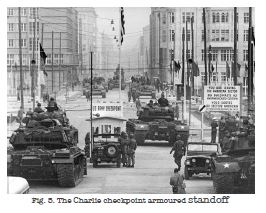

Tensions flared again in 1958, following a decade of relative calm. For the next three years, the Soviets blustered and threatened the Allies, emboldened by the successful launch of the Sputnik satellite the year before during the “Space Race” and humiliated by the seemingly endless influx of refugees from east to west (nearly 3 million after the end of the blockade, many of them young skilled workers such as physicians, teachers, and engineers). Summits, conferences, and other forms of negotiation have come and gone with no results. In October 1961, the U.S. chief of mission in West Berlin, Alan Lightner, was stopped in his car by East German police. This prevention of access for American officials to East Berlin caused a standoff between American and Soviet tanks, which then faced off at Checkpoint Charlie for many hours. Both sides stared each other down waiting for their enemy to fire – the consequent potential for World War 3 was eventually averted when President John F. Kennedy contacted Nikita Khrushchev and convinced him to withdraw his tanks. The American tanks also backed away soon after.

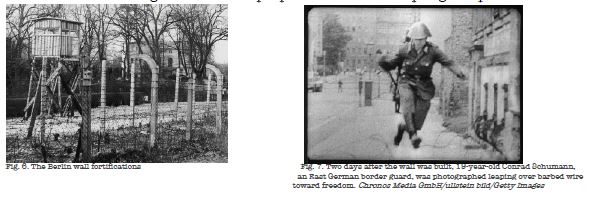

Meanwhile, the refugee influx began. Around 19,000 people left the GDR via Berlin in June 1961. 30,000 people left the next month. 16,000 East Germans crossed the border into West Berlin in the first 11 days of August, and 2,400 more followed on August 12—the highest number of defectors ever to leave East Germany in a single day. To prevent further losses, East Germany decided to close the border, and that’s where the Berlin Wall came in. Extending for 43 kilometers through Berlin, and a further 112 through East Germany, the initial barrier consisted of barbed wire and mesh fencing. Some Berliners escaped by jumping over the wire or leaving from windows, but as the wall expanded, this became more difficult. By 1965, 106 kilometers of 3.6-meter-high concrete barricades had been added topped with a smooth pipe to prevent climbing. Over the coming years, the barrier was strengthened with spike strips, guard dogs, and even landmines, along with 302 watchtowers and 20 bunkers. A parallel fence in the rear set off a 100-meter area called the death strip. There, all buildings were demolished and the ground covered with sand to provide a clear line of sight for the hundreds of guards ordered to shoot anyone attempting to cross. Nevertheless, nearly 5,000 people in total managed to flee East Germany between 1961 and 1989. Some were diplomats or athletes who defected while abroad, but others were ordinary citizens who dug tunnels, swam across canals, flew hot air balloons, or even crashed a stolen tank through the wall. Yet the risk was great. Over 138 people died while attempting escape.

The Mistake

On November 8th, 1989, GDR official Gerhard Lauter was tasked with drafting looser travel regulations, meant to be a temporary pressure release. The new rules were finalized less than a day later, and read: “Private trips abroad can be applied for without conditions. Permits are

issued on short notice.” “Without conditions.” That’s the key phrase here. This meant the strict application requirements were eliminated, and anyone who wanted could leave East Germany and come back. That afternoon, the updated regulations were handed to government spokesman Günter Schabowski, just as he was about to begin a routine press conference.

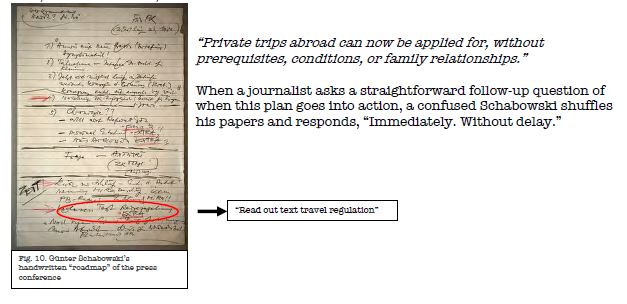

He had no time to review them before sitting in front of cameras. And as you can see from his handwritten “roadmap” of the press conference (Fig. 9), he scribbled in a reminder to announce them at the very end. And on live TV at 6:53 PM on November 9th, he read the relaxed travel laws, for the first time, out loud.

The thing is, if Schabowski had taken the time to read the new rules, he would have seen this on the last page: The new regulations were meant to go into effect the following day, in an orderly manner, when the passport offices were open. What happened next can only be described as a chain reaction. By 7:05 PM, the AP wire had already gone out: East Germany opens borders. And both East and West German nightly news reports announced the stunning policy reversal. East Berliners began gathering at the wall, and security officers tried to let them through slowly. But the final nail in the coffin came at 10:42 pm, when this broadcast triggered a mass rush: They actually weren’t yet. But by this point, there was no going back. Tens of thousands of Berliners stormed the Wall, saying they heard on the news that they could cross. The outnumbered East German border guards were completely overwhelmed.

Conclusion

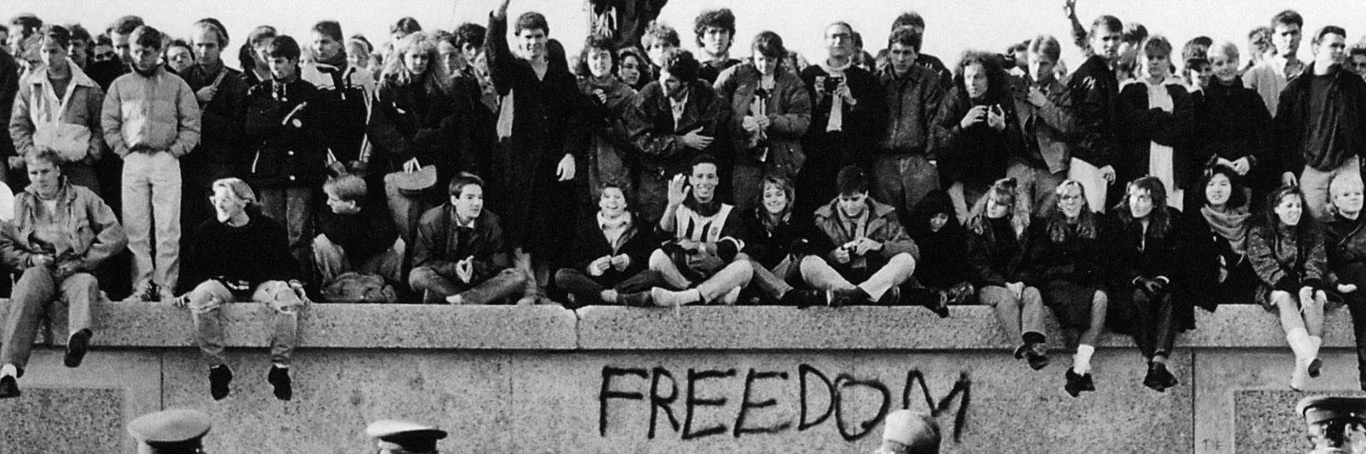

The spokesman for East Berlin’s Communist Party declared a change in his city’s ties with the West on November 9, 1989, as the Cold War started to thaw across Eastern Europe. People of the GDR were free to cross the country’s borders starting at midnight that day, he said. Berliners from both sides flocked to the wall, shouting “Tor auf!” (“Open the gate!”) drinking beer and champagne. They poured through the checkpoints at 12 a.m. Over 2 million people from East Berlin traveled to West Berlin that weekend to take part in a festival called “the biggest street party in the history of the world” by one journalist. People knocked down sections of the wall with hammers and picks (known as “mauerspechte,” or “wall woodpeckers”), while cranes and bulldozers pulled down section after section. The Berlin Wall was demolished soon after, and the city was reunited for the first time since 1945. And it all happened unintentionally. The result of a rushed plan and a botched announcement, delivered in a small room at the end of a boring press conference.

“Forget not the tyranny of this wall … nor the love of freedom that made it fall…” – Unknown, Graffiti on the Berlin Wall.

Sources

– https://www.history.com/topics/cold-war/berlin-wall

– https://ed.ted.com/lessons/the-rise-and-fall-of-the-berlin-wall-konrad-h-jarausch#watch

– https://www.vox.com/search?q=fall+of+the+berlin+wall